How many times have you heard about the curse of Tutankhamun, about the inscription that Howard Carter supposedly found on the door of his tomb, warning that Death will come on swift wings to those who disturb the pharaoh’s peace, or Death will strike with its fear anyone who disturbs the pharaoh’s rest? In reality, Carter made no mention of this in his diary, and it was the death of Lord Carnarvon, his patron, that sparked the legend of the revenge of the young pharaoh. Who was Lord Carnarvon? Let’s find out.

His name was George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert, and he was born in Hampshire, England, in 1866. Obviously, he came from a noble family, the son of a conservative politician named Henry Herbert, Earl of Carnarvon, which is why the newborn immediately received the title of Lord Porchester. He left his residence, the splendid Highclere Castle (immortalized in the television series Downton Abbey), to study at the prestigious schools of Eton and Trinity in Cambridge, succeeding his father as the county’s title holder in 1890.

Five years later, he married Almina Victoria Maria Alexandra Wombwell, the illegitimate daughter of banker Alfred de Rothschild, in the same St. Margaret’s Chapel that used to host the weddings of illustrious personalities, such as Catherine of Aragon or Winston Churchill, and also some notable burials, like those of the sailor Walter Raleigh and the poet John Milton. It’s not surprising that someone of his lineage accepted such a union because, feelings aside, connecting with the Rothschild family worked well for him to pay off the substantial debts left by his father, thanks to the half-million pounds added by the dowry.

Resolved the economic issue, Carnarvon invested part of his fortune in thoroughbred racehorses, expanding it. This allowed him to lead a carefree and stylish life typical of the affluent class of the time, which included two hobbies that would shape his future. One was being what was called a sportsman; the other was an interest in Egyptology, an archaeological branch that was experiencing a period of splendor since Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt a century earlier. Interestingly, both interests would combine to make this aristocrat enter history, which would otherwise only interest horse racing fans.

The fashionable sport in the first two decades of the 20th century was motor racing. All the wealthy who could afford it bought a car and raced at full speed on those precarious road networks designed for carriages, not motor vehicles, sometimes ending tragically. Carnarvon could have been one of the first to lose his life, but he was lucky, at least partially.

In 1901, the accident he suffered while avoiding an ox cart during a visit to Germany (where he had moved because the speed limit was higher than the six miles per hour allowed in his homeland) was so severe that it caused significant injuries.

When he was discharged from the hospital, the consequences were evident. The broken wrist, concussion, and wounds to the mouth were left behind, along with a temporary loss of vision. However, in return, he was partially disabled due to burns on his legs, and his lungs were permanently damaged, making breathing difficult. That’s why doctors advised him to leave the damp climate of England and find a warmer, drier place to reside.

That’s where Egypt, his other great passion, came into the picture. He started traveling there every year to spend the winter, taking the opportunity to acquire antiquities with which he formed a private collection. Lacking formal training in the field, he relied on the advice of Sir William Garstin, an advisor to the Ministry of Public Works, who even secured an excavation license for him. He only needed a man on the ground, someone with the knowledge he lacked and, above all, who was not physically impaired. So, he sought help from Gaston Maspero, a French Egyptologist who headed the Egyptian Antiquities Service. The name he proposed was Howard Carter.

Carter also lacked university education but had worked as an assistant to the famous archaeologists Flinders Petrie and Edouard Naville. Working alongside them, he not only learned everything he needed but reached such a level that he became the Inspector of Antiquities in Cairo. At that moment, he was unemployed after a dispute with some French looters, so he gladly accepted Carnarvon’s patronage, and they would be together for sixteen years.

They began excavating in Deir el-Bahari in 1907 and moved to the Valley of the Kings in 1914. However, the First World War forced them to stop until 1917 when they resumed activity, continuing until 1922. By then, the lack of results and the conviction that the valley had nothing more to offer had disappointed the crippled aristocrat so much that he decided to end his archaeological hobby; that would be his last year. And as that year was coming to an end, on November 4, he received a telegram from Carter at his London home, announcing that he had made a “marvelous discovery”, a “magnificent tomb with intact seals”.

The previous month, Carter had asked for an extension, assuming the expenses himself, convinced that there was something there. Indeed, on October 22, he found steps leading to a sealed entrance. He broke it down with pickaxe blows to access a narrow passage covered in debris, a sign that looters had been there before, but his intuition told him that maybe they hadn’t achieved their goal. Following the usual protocol, he sealed the entrance, notified the authorities of the discovery, and informed his sponsor.

Carnarvon, accompanied by his daughter Evelyn, visited the tomb, named KV-62, before its official opening. They cleared new steps from the entrance and were thrilled to see Tutankhamun’s scarab, a pharaoh about whom little was known. The euphoria faded when they found new signs of looters and cartridges with the names of other kings, indicating that perhaps it was not a tomb but a simple repository of funerary offerings.

But the next day, they discovered another door; it had a broken seal, but from the hole made, it was impossible for a thief to have passed through. And as Tutankhamun’s name was again readable, they regained optimism. Carter expanded that hole with a hammer and peered through with a candle. The scene has been recounted thousands of times:

“Do you see anything worthwhile?” -an eager Carnarvon asked.

“Yes, marvelous things”, the other replied in astonishment.

Then, the patron looked through with an electric lantern and was ecstatic. A visit to the Archaeological Museum of Cairo is not enough to understand the excitement that the two partners must have felt: chests, statues, a couch, a throne, four war chariots, hundreds of small coffers, alabaster vessels… and two more sealed and inviolate doors, one of which they had to pass through by crawling through a hole, Carnarvon and Evelyn included, although that would be later; the point is that it led to the burial chamber, where an imposing wardrobe housed three coffins, one inside the other, in the last of which rested Tutankhamun’s mummy with its precious gold mask.

The news spread worldwide, and the sensational find was attributed to Carnarvon, not so much for financing the campaign, but because he wrote a letter to the British Museum informing them, and he did it in the first person singular. Additionally, Carter became a target for the criticism of many archaeologists who accused him of not having a degree. Carnarvon had no patience for the slow pace required by archaeological excavations and returned to England while work on the tomb was being completed: debris removal, photography, cataloging, preservation treatments…

Carter and Carnarvon had a serious disagreement in February 1923 when the former insisted on handing over the treasure to the Egyptian authorities, as opposed to the latter who expected to keep a portion, more for prestige than money since the reimbursement of expenses was guaranteed (in 1939, the Egyptian government would expropriate the tomb and its contents, paying compensation to the Carnarvons). They eventually reconciled and resumed work, which had been interrupted for this reason. But their fruitful partnership was about to end, and the legend was about to begin. And the blame fell on a mosquito.

After one of those discussions, Carnarvon had left Carter’s house, where he was a guest, to stay at the Hotel Winter Palace in Luxor. On the morning of March 19, he woke up with a fever of forty degrees, which he attributed to an infection caused by a mosquito bite he got while shaving. Ignoring medical advice to rest, avoid alcohol, and take the prescribed medication, over the week, he worsened until he had to be transported to Cairo, where he died in a room at the Continental-Savoy Hotel on April 5.

His death opened the door to the story of the curse of Tutankhamun, a goldmine for sensationalist press, which began to associate alleged deaths of people who had worked on the excavation: from some Egyptian workers to curious visitors of the tomb, including Carter’s assistant and Carnarvon’s own brother. These deaths—eight out of a total of fifty-eight people involved—did not occur all at once but stretched over several years, which is quite natural. Carter himself was “killed” by an American newspaper that confused him with someone who had the same name.

The matter grew in size, acquiring increasingly fantastical details never proven: it was said that in his last breath, Carnarvon had shouted that a crow (associated with the goddess Nekhbet) was digging its claws into his face, that at that moment, his dog in London also died, that the lights went out all over Cairo, that his canary was devoured by a cobra, and that a wound exactly in the same spot on the neck as the alleged grain was found in the pharaoh’s mummy. Moreover, many psychics and spiritualists, popular in those years, claimed to have predicted it. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, entirely credulous in such matters due to the desire to contact his prematurely deceased son, echoed the stories.

At the time, efforts were made to debunk the existence of the curse, and the most obvious argument was that the main culprit of violating Tutankhamun’s eternal rest, Howard Carter, not only was unaffected but became a global figure in archaeology and lived until 1939. We could add the thousands and thousands of tourists who have visited the site since then.

There were several explanations given for Lord Carnarvon’s end. Hypotheses such as septicemia and mycotoxins (fungi that might have been in the tomb) were considered, but currently, it is believed that Lord Carnarvon’s death had nothing to do with that small hypogeum in the Valley of the Kings.

A study in the medical journal The Lancet suggests that his death was due to multi-organ failure caused by pneumonia, originating from erysipelas (a streptococcal infection affecting the skin and lymphatic vessels), to which he would be particularly susceptible due to his weakened immune system.

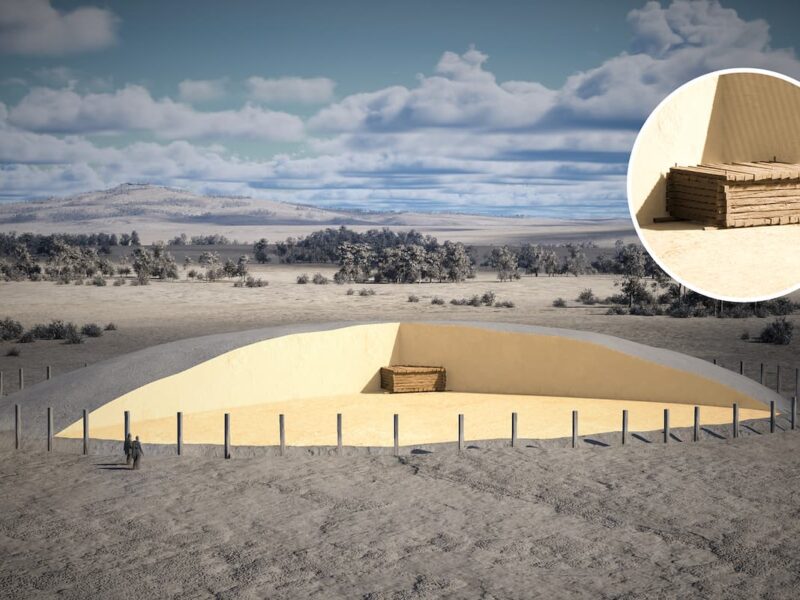

Lady Almina, his widow, repatriated the mortal remains to England and buried them on a hill on her Hampshire estate called Beacon Hill, in a simple burial consisting of a gravestone on the grass surrounded by a fence. It is said that at the end of the funeral festivities, a medium approached her son, Henry Herbert, and warned him never to approach his father’s grave to avoid the curse… and the young new Earl heeded her advice.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on December 15, 2018. Puedes leer la versión en español en Lord Carnarvon, el mecenas de Howard Carter cuya muerte dio origen a la leyenda de la Maldición de Tutankamón

Sources

Howard Carter y A.C. Mace, The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen: Discovered by the Late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter | G. Elliot Smith,Tutankhamen & The Discovery of His Tomb | Brian Fagan, Lord and Pharaoh: Carnarvon and the Search for Tutankhamun | Ann M. Cox, The death of Lord Carnarvon | Wikipedia

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.