To many, it may seem strange that Egypt is now one of the world’s largest wine producers, with an annual quantity similar to that of Britain. However, the fact is that wine production has been linked to Egypt for many centuries.

Obviously, it was not the ancient Egyptians who invented it. Archaeologists have traced its beginnings to an extensive area south of the Caucasus, between present-day Georgia, Turkey, Armenia, and Iran, around 8000 to 5000 BCE.

During the Bronze Age, both grape cultivation and wine production spread across Asia and Europe, reaching China and the Iberian Peninsula, where the Phoenicians found vineyards upon arrival. And, of course, the new beverage became part of trade and merchant routes throughout the ancient world.

In Egypt, a wine industry emerged as early as the 27th century BCE, likely imported from Canaan during the third dynasty.

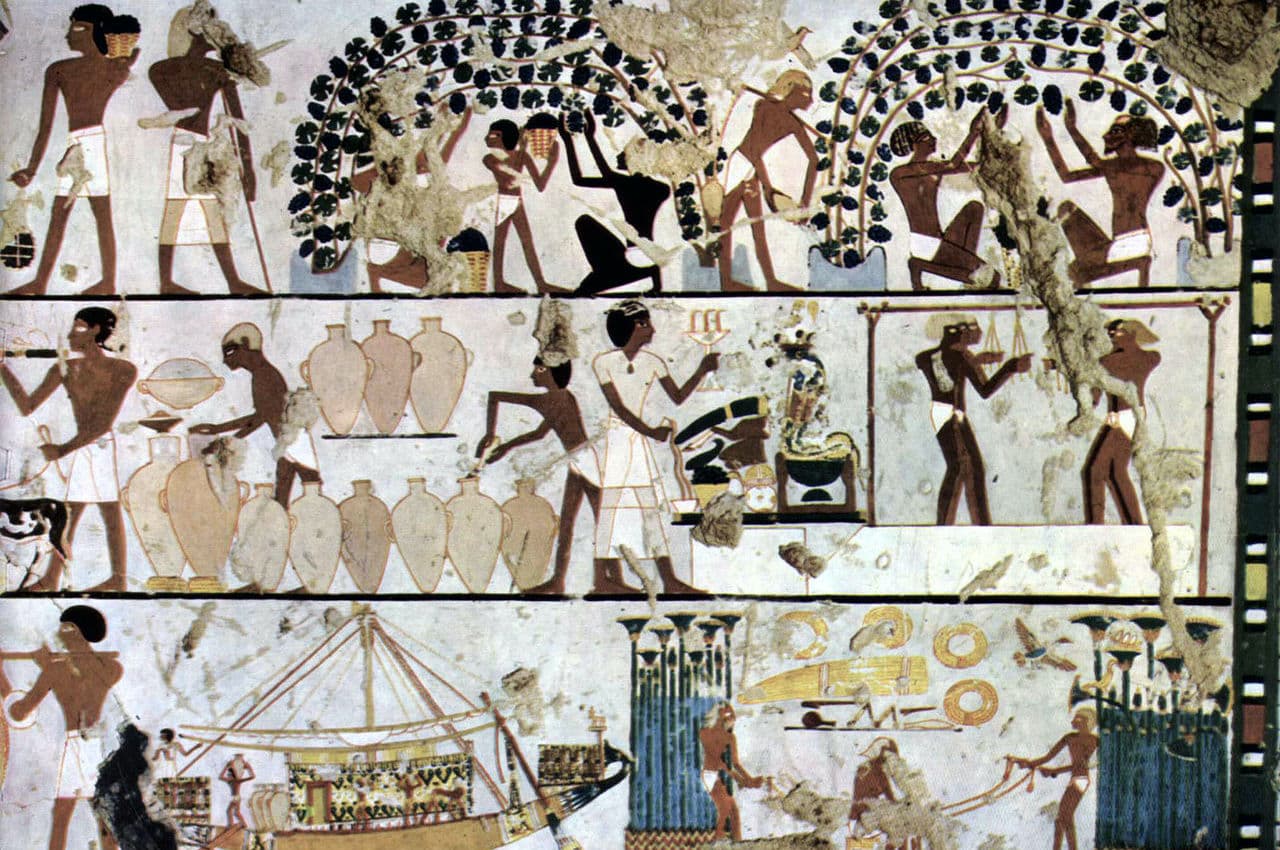

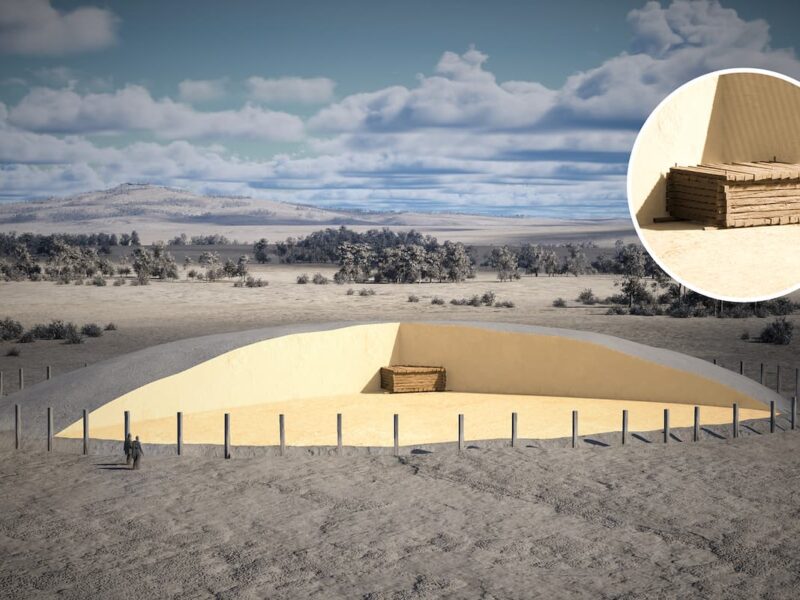

The Egyptians controlled wine routes between 1550 and 1070 BCE. To transport and preserve wine safely, they introduced standardized amphorae sealed with reed and mud joints and coated with pitch inside, preventing spoilage during long journeys. Some of these amphorae, still containing wine, were found in the tombs of Semerkhet and Tutankhamun.

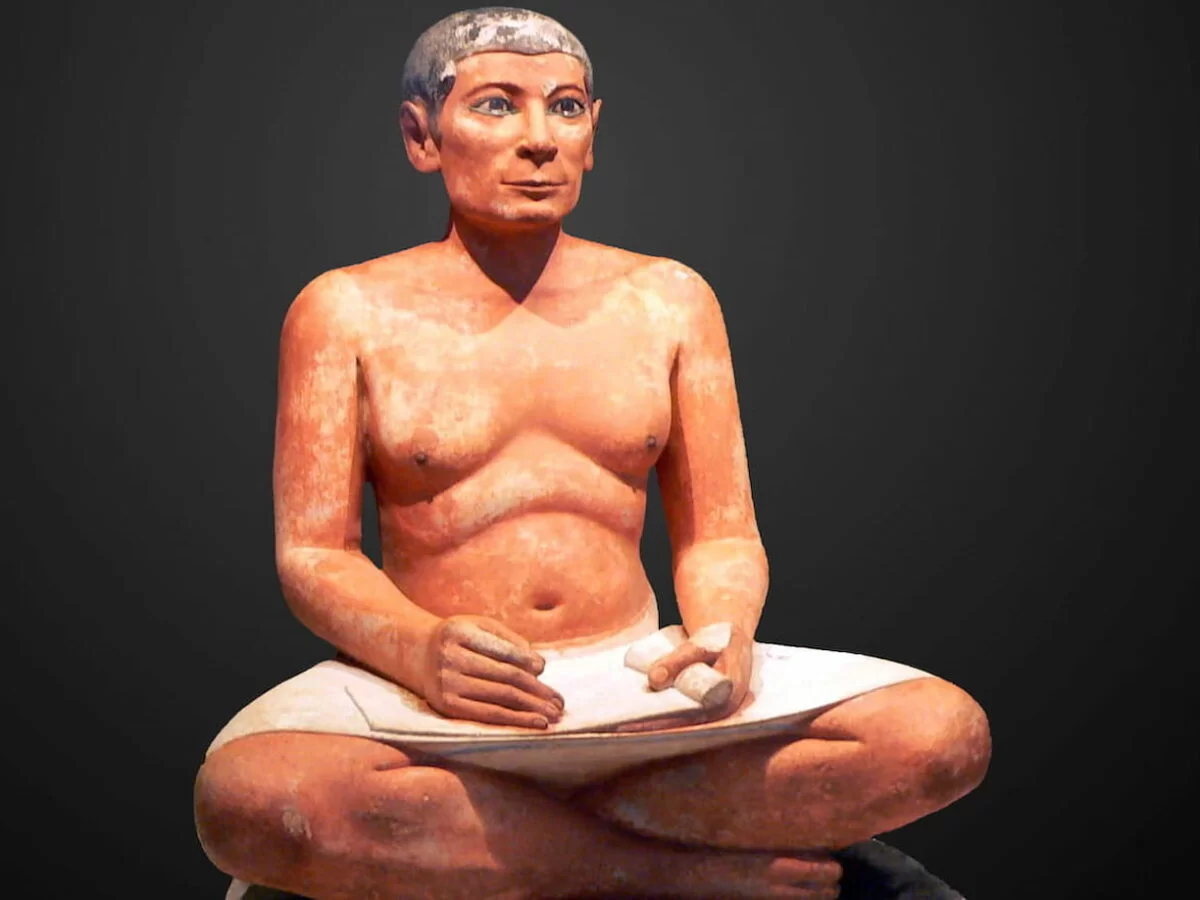

The Egyptian people preferred beer, with wine reserved for the pharaoh, priests, and the upper classes, except on special occasions such as the festivals of the goddess of the grape harvest, Renenutet, or the festival of Hathor. According to Plutarch, the Egyptians believed that wine was:

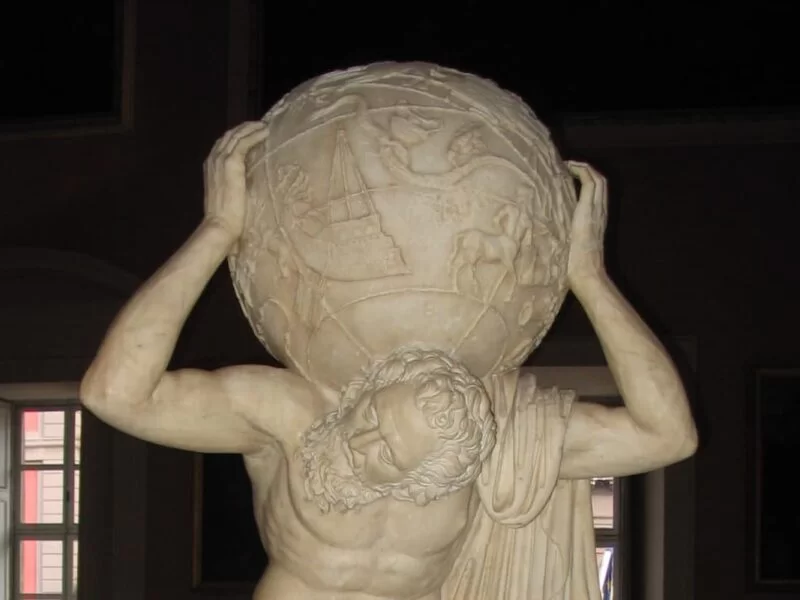

the blood of those who had once fought against the gods, and from whom, when they fell and mixed with the Earth, they believed vines had sprouted. This is why drunkenness makes men lose their senses and go mad, as they then fill themselves with the blood of their ancestors.

Plutarch, On the Worship of Isis and Osiris 6

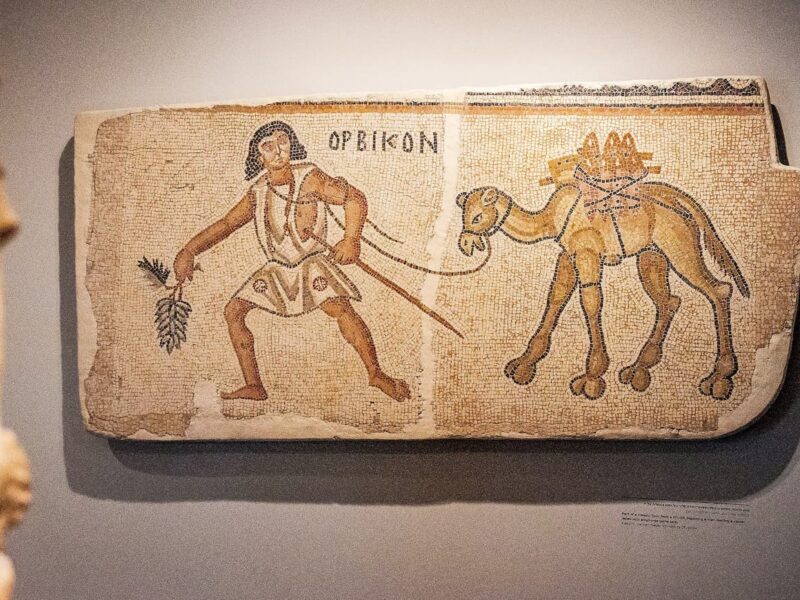

With the wine trade came branding, initially identifying only the contents of the amphorae. The oldest known is a Babylonian cylindrical seal from about 6,000 years ago, used to stamp amphorae indicating they contained wine (depicting a group of people in a joyful attitude, as expected).

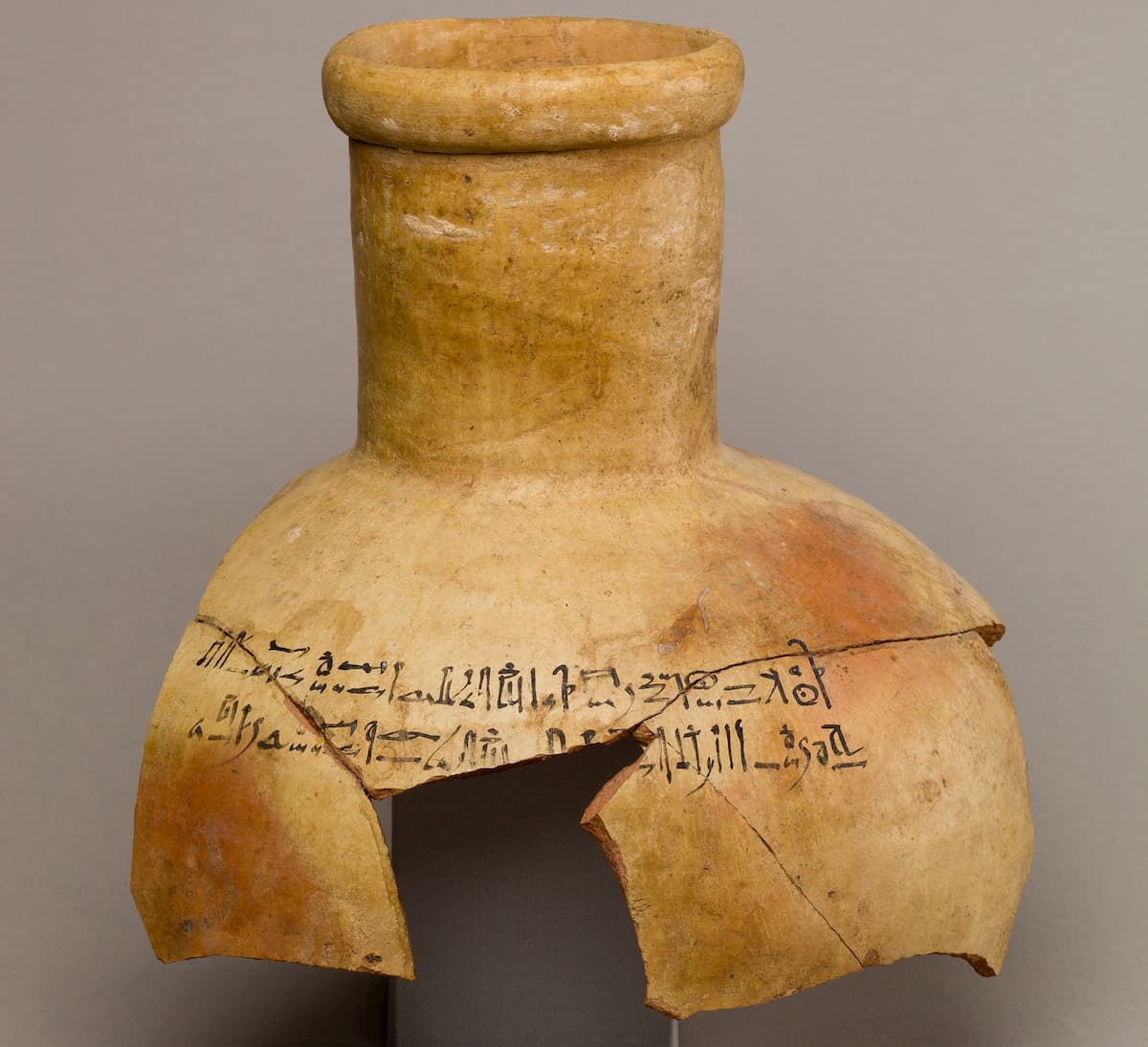

But the Egyptians added a series of information to these marks, creating what are considered the oldest known wine labels.

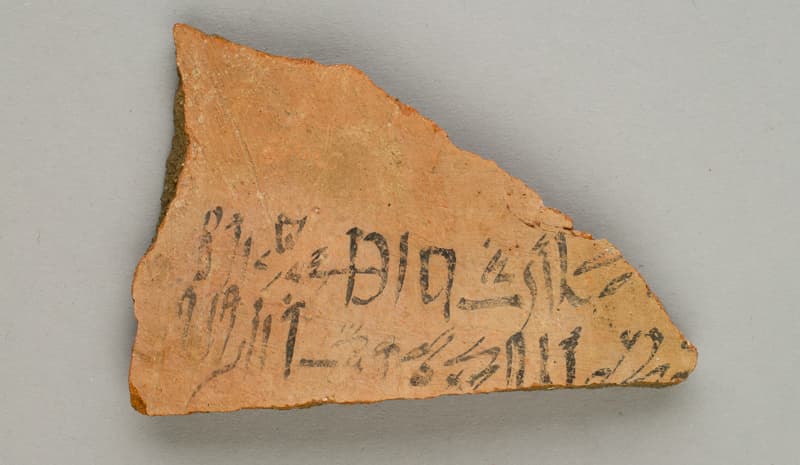

The labeling on amphorae was done directly on wet clay, or ostraca (handwritten limestone, earthenware, or ceramic) was used.

They included one or more of the following details:

- The year the wine was presented to the pharaoh, usually coinciding with the production year.

- Its quality, ranging from genuine to good and very good.

- The occasion it was presented, for example, New Year festivals.

- The geographical region where it was produced.

- The name of the vineyard owner (mostly bearing the name of the corresponding pharaoh, as the vineyards were mostly royal property).

- The name or title of the person offering the wine to the pharaoh.

- The name of the chief viticulturist.

- Occasionally, the capacity of the container.

Interestingly, researchers examining the wine amphorae found in Tutankhamun’s tomb confirmed that the Egyptians kept a record of years with better harvests, as only wine from specific years was buried with the pharaoh.

They also appreciated aged wines, as the content of some amphorae was 200 years old when deposited as funerary offerings in the tombs.

The oldest of all were found in the tombs of King Scorpion and Narmer in Abydos, from the late fourth millennium BCE.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on December 21, 2018. Puedes leer la versión en español en Cómo los antiguos egipcios inventaron las etiquetas para el vino

Sources

P.E. McGovern, Wine of Egypt’s Golden Age: An Archaeochemical Perspective | Wine Making in Ancient Egypt | Mu-Chou Poo, Wine & Wine Offering In The Religion Of Ancient Egypt | Vinography | Vinepair | Winedesign | Wikipedia

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.