While there is no shortage of examples – some very famous – generally, women have not been prominent in military history because, traditionally, the profession of arms has been exercised by men. This is why cases in which women have led battles or led armies often attract attention. One of the most significant, yet less known, was that of the Welsh Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd, in the midst of the Middle Ages.

There are quite a few female names linked to combat actions, like Juana García de Arintero, who wielded a sword in medieval times, the Breton corsair Jeanne de Belleville, the Japanese Tomoe Gozen, or the most famous of all, Joan of Arc.

There were also cases in Great Britain, although attention there focuses primarily on the resistance of Queen Boudicca against the Roman occupation or the story of Petronilla de Grandmesnil, captured after following her husband – wearing armor and all – in the rebellion against King Henry II. Just a few decades before the episode of the latter, the epic reaction of Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd took place to prevent the Norman invasion of Wales, something unique in the annals of that nation.

The name of this heroine should not be taken literally because in Welsh, it means Gwenllian daughter of Gruffydd. In other words, she was a princess since Gruffudd ap Cynan was the ruler of Gwynedd, one of the six small kingdoms into which the current country of Wales was divided during the Middle Ages.

Founded in the 5th century by a predynastic monarch, Cunedda, after the departure of the Romans from Britannia, it was the land of the Venedotia, a name that grouped Celtic tribes like the Ordovices, Gangani, and Deceangli, expanding over the following centuries to encompass the entire north of Wales, including the island of Anglesey.

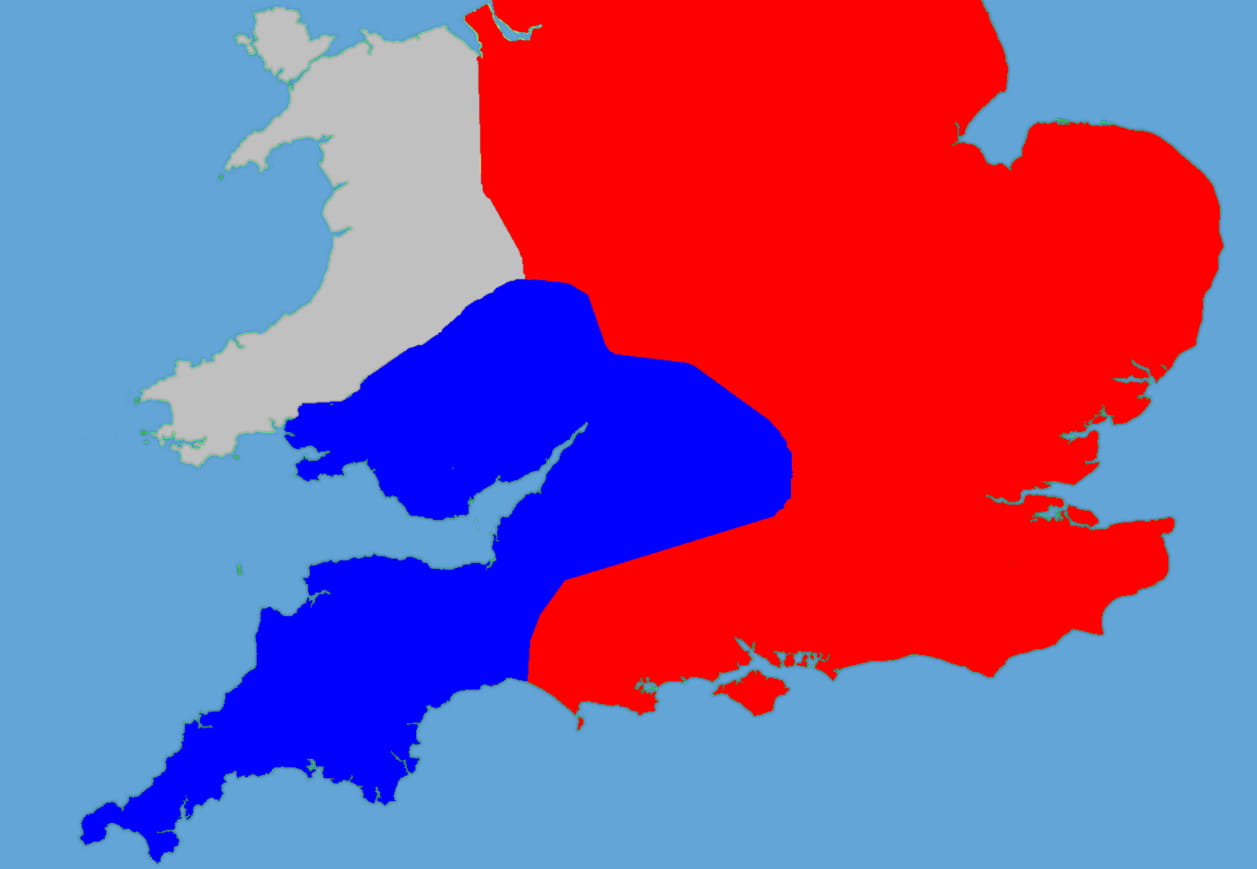

The Irish Sea constituted most of Gwynedd’s border except in the southern half, where it bordered the kingdom of Powys. This made it reasonably protected against external danger since the sea on one side and the mountains on the other served as natural defenses, although foreign interference sometimes deposed the kings, often taking advantage of internal discord. In 1066, the Normans, who had just conquered England, also occupied Gwynedd in one of those turbulent periods.

At that time, Bleddyn ap Cynfyn ruled instead of his half-brother Gruffydd, who was the legitimate heir. Gradually, Gruffydd gained supporters from his exile, seizing more and more territory until forcing Bleddyn to retreat to Powys, where he also held the crown. Gruffydd thus regained his throne, albeit briefly, as the death of his ally, Ælfgar of Mercia, and the betrayal of some of his own led to his assassination. He was replaced by Count Harold Godwinson, who has gone down in history as Harold II of England.

Harold was defeated by the Norman William the Conqueror, who, unstoppable, not only took over English territory but also set his sights on Wales. The Norman nobles divided the kingdom, and it seemed that a long period with their presence there was opening up, but in 1094 a general uprising occurred, and in 1136, they were overwhelmingly defeated by Owain Gwynedd, who launched a victorious reconquest campaign until his death in 1170.

Then the civil war for succession broke out. But let’s pause in the narrative to focus on the family of the deceased. He was the firstborn son of Gruffydd ap Cynan and Angharad and, therefore, the brother of Cadwallon, Gwynedd, and Cadwaladr, who took sides in two opposing blocks for the inheritance. They had five sisters: Mared, Rhiannell, Susanna, Annest, and the youngest, Gwenllian, who is the one of interest here. She was born in the year 1100 in Aberffraw, a locality on the southwest coast of Ynys Mon (current Anglesey), which was then the capital of the kingdom of Gwynedd since the year 860 and also gave its name to the House of these figures.

According to accounts, Gwenllian was of proverbial beauty, and that’s why she dazzled Gruffydd ap Rhys, prince of the neighboring southern kingdom of Deheubarth, who in the year 1113 was visiting Gwynedd since his father had been an ally of the young woman’s father. As expected, they fell in love, and after a short courtship, they married (note that she was no more than thirteen years old). Together they settled in Dinefwr and had four children: Morgan, Maelgwyn, Maredudd, and Rhys Fychan; the first three died young, at twenty, seventeen, and twenty-five years old; only the third had a long life.

Gruffydd recruited an army to attack the Norman castles in his occupied kingdom of Deheubarth, where settlers from not only Normandy but also England – which was under Norman rule, let’s remember – and Flanders had established themselves. Since they did not have a territorial reference point, rebel troops moved from one place to another, and this included the royal family, with Gwenllian following her husband wherever he went, taking advantage of the cover provided by mountains and forests.

In such conditions, they opted for a guerrilla tactic of surprise attacks and rapid withdrawals, making it very difficult for the Normans to defend themselves since their strength lay in fortifying themselves in the impregnable castles scattered throughout the kingdom. In addition, the rebels not only had the support of the House of Aberffraw but also that of the House of Dinefwr, which was plundered by the Normans because it was the one that had previously ruled Deheubarth (by the way, the Tudors descend from Dinefwr).

In 1136, the aforementioned great uprising occurred, taking advantage of the chaos in England due to the succession to the English throne. It all began when Stephen of Blois, Duke of Normandy, overthrew his cousin Matilda and ascended to the throne but not without a period of civil war that has gone down in history with the graphic name of the Anarchy, which lasted from 1135 to 1153. This affected the governance of Wales, whose local leaders were deprived of central authority, thus inciting the people to revolt.

It started in the south with the campaign of Hywel ap Maredudd, lord of Brycheiniog (Brecknockshire), against the Normans of Gower (a mark in the southern part of Deheubarth), whom he defeated in the Battle of Llwchwr, near Swansea, surprising them with a whole army instead of the poorly armed bands they expected. Half a thousand Norman soldiers perished in the clash, and the victory resonated throughout Wales, encouraging others to rise in arms as well. Among the first were Gruffydd ap Rhys and his wife Gwenllian, who joined forces with her father, and together they gained sympathizers as it became known that their princes were distributing land and property taken from the hated invaders among the Welsh.

The Normans reorganized and launched counterattacks to try to suppress the rebellion and aid their leader, Maurice, who began gathering them at Cydweli Castle, in the current town of Kidwelly, where he had taken refuge fleeing from Llwchwr. Informed of the danger and in the absence of her husband, who was with her father in the north, Gwenllian took command of a diminished troop and besieged the castle. There were around two hundred men, insufficient for her conceived plan: to use half to cut off the supply line and the rest to stop the reinforcements arriving to join Maurice.

Even so, it seems that what went wrong was an unforeseeable event: a traitor. None other than one of the tribal leaders, named Gruffydd ap Llewellyn. Thus, it was the Normans who surprised the Welsh, not the other way around, and Maurice himself allowed himself to leave the protection of his battlements to participate in the slaughter. Gwenllian was thrown from her horse and beheaded on the spot, losing her two older sons, whom we mentioned earlier: the firstborn, Morgan, died trying to defend her, and the other, Maelgwyn, was captured and executed.

The scene of that tragic clash is now known as Gwenllian Maes (Gwenllian’s Field), and there is a spring there that, according to legend, springs right where she lost her life. It is not trivial because Gwenllian’s death inflamed the spirits of all of Wales, and it was then that the mentioned uprising spread, putting the entire country at war.

In that sense, Gruffydd ap Rhys had the opportunity to avenge the death of his family and also helped by his father-in-law, as both achieved a crushing victory over the enemy at Crug Mawr, near Cardigan, thus controlling the entire western region of Ceredigion.

Perhaps they were the ones who initiated a tradition of Welsh soldiers that lasted a long time: that of shouting Vengeance for Gwenllian! when launching into battle. Of course, these were very propitious times for the creation of epic myths; it is not uncommon to see Gwenllian represented in art riding a chariot and waving her long red mane in the wind. In reality, in the Middle Ages, combat was no longer carried out this way, but she was seen as if she were a reincarnation of Boudicca.

Gruffydd, Gwenllian’s father, died the following year, and that was when his sons Owain and Cadwaladr abandoned the campaign against the Normans to start a civil war to succeed their father. However, his work, considered in his later years a kind of golden age, allowed the kingdom of Gwynedd to remain safe despite everything. In the end, a compromise was reached: Owain ascended the throne, leaving his brother Anglesey and Ceredigion, although they would later face each other again.

As for Gruffydd ap Rhys, Gwenllian’s widower, he also died in 1137, although it is unknown under what circumstances. His heir was Anarawd, a son he had had from a previous marriage (four in total, with another named Cadell and three girls, Gwladus, Elizabeth, and Nest), as he was older than the survivor born to Gwenllian, Rhys. However, he would also reign later; and he honored his mother by naming two of his daughters Gwenllian.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on December 27, 2018. Puedes leer la versión en español en Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd, la princesa medieval galesa que lideró un ejército contra los invasores normandos

Sources

John Davies, A History of Wales | David Walker, Medieval Wales | R. R. Davies, The age of conquest: Wales 1063–1415 | K. L. Maund, GrIuffudd Ap Cynan: A Collaborative Biography | Ginny Burgues, Remarkable Women: The Life and Times of Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd | Laurel A. Rockefeller, Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd: Una obra en tres actos | Wikipedia

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.