Passenger pigeons, scientifically known as Ectopistes migratorius, were once the most abundant birds in North America, and possibly the world. Their name, derived from the French passager meaning “passenger”, reflects their migratory habits.

These birds traveled in enormous flocks that, according to historical accounts, darkened the sky during their passage, and their wing beats produced a thunderous noise accompanied by wind.

That amazing spectacle can no longer be witnessed, as passenger pigeons went extinct more than a century ago. The last wild passenger pigeon was sadly shot by a boy in Ohio in 1900.

But before that, at their peak, it is estimated that the population of passenger pigeons ranged between 3 billion and 5 billion individuals.

Their weight ranged from 260 to 340 grams, and males could reach 41 centimeters in length. They had blue-gray heads, napes, and necks with iridescent feathers that varied in color depending on the light. The upper parts of their wings and backs were pale gray or slate with olive-brown tones.

The wings had black spots and white edges, with the central tail feathers being grayish-brown and the rest white. Females were smaller and had duller colors.

Ornithologist and naturalist John James Audubon observed and described in 1813 a migration in which the birds passed in such dense multitudes that they completely covered the sky and daylight was darkened.

In 1866, a flock spotted in southern Ontario was described as 1.5 kilometers wide and 500 kilometers long, a spectacular and unsettling column of birds that took 14 hours to pass and might have contained up to 3.5 billion birds.

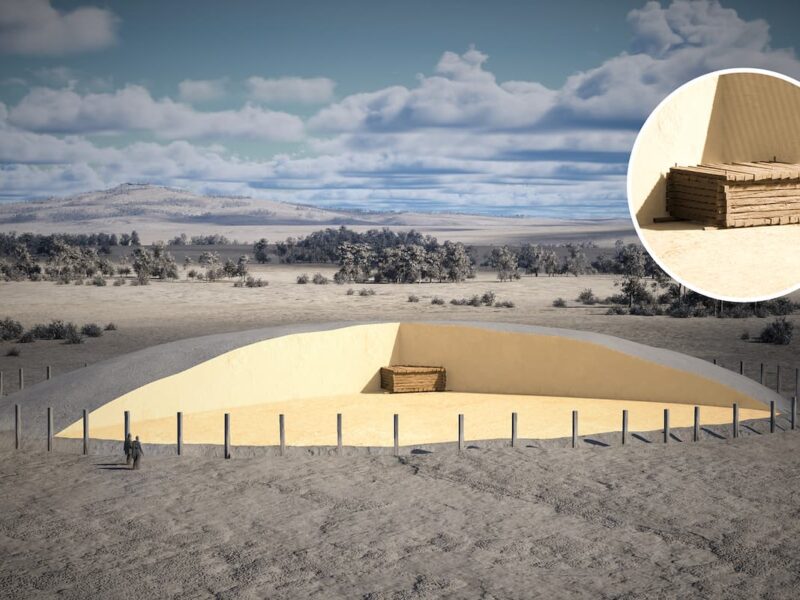

Passenger pigeons were very social birds, not only in their flying behavior but also in their feeding and reproduction. They formed large colonies where they fed on fruits, seeds, and acorns, and bred in communal nests that crowded the treetops in the deciduous forests of North America.

Their migratory behavior was constant and nomadic, always in search of food and suitable nesting places. During winter, their range extended from Arkansas and North Carolina to Texas and the Gulf Coast, although sometimes they ventured further north to Pennsylvania and Connecticut. Passenger pigeons preferred large swamps with alder trees for roosting, and in their absence, they settled in dense forest areas with pines.

They were capable of flying at speeds of up to 100 kilometers per hour, moving swiftly through both forests and open spaces. The flocks were highly coordinated, able to change direction en masse to avoid predators, which allowed them impressive maneuverability in the air.

The relationship of passenger pigeons with humans began relatively benignly, with hunting by Native Americans for food. However, with the arrival of European settlers, it intensified significantly, becoming a cheap and accessible food source, leading to indiscriminate and large-scale hunting throughout the 19th century.

Massive deforestation also played a crucial role in their decline. The destruction of the large forests that served as their primary habitat and nesting sites drastically reduced the available areas for these birds. Between 1800 and 1870, the passenger pigeon population began a slow decline, followed by a rapid decrease between 1870 and 1890.

By 1900, the last wild passenger pigeon was shot in southern Ohio, although the extinction would not be complete until 1914 with the death of Martha, the last known passenger pigeon, at the Cincinnati Zoo.

The case of passenger pigeons has become a paradigmatic example of human-induced extinction. It serves as a reminder of the fragility of ecosystems and how quickly a species, no matter how abundant, can be driven to extinction through exploitation and habitat destruction.

Sources

Chelsea Harvey and Elizabeth Newbern, 13 Memories of Martha, the Last Passenger Pigeon | Barry Yeoman, Why the Passenger Pigeon Went Extinct | Errol Fuller, The Passenger Pigeon | Mark Avery, A Message from Martha: The Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon and Its Relevance Today | Wikipedia

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.