At the border between Turkey and Syria, near the mouth of the Orontes River on the Mediterranean Sea and about 30 kilometers north of ancient Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra), lies a mountain that has played a prominent role in the history of the region. Today it’s called Jebel Aqra (Mount Kel in Turkish), but it has had many other names in different epochs.

Situated practically on the coast, its slopes descend directly into the sea, leaving little space for small sandy coves. With its 1,717 meters of altitude, it has always been a landmark for sailors.

It has the peculiarity of seemingly attracting storms, given its proximity to the sea and its height, making them frequent on its summit and slopes. Thus, since ancient times, it has been considered a dwelling place of the gods, similar to the Greek Olympus.

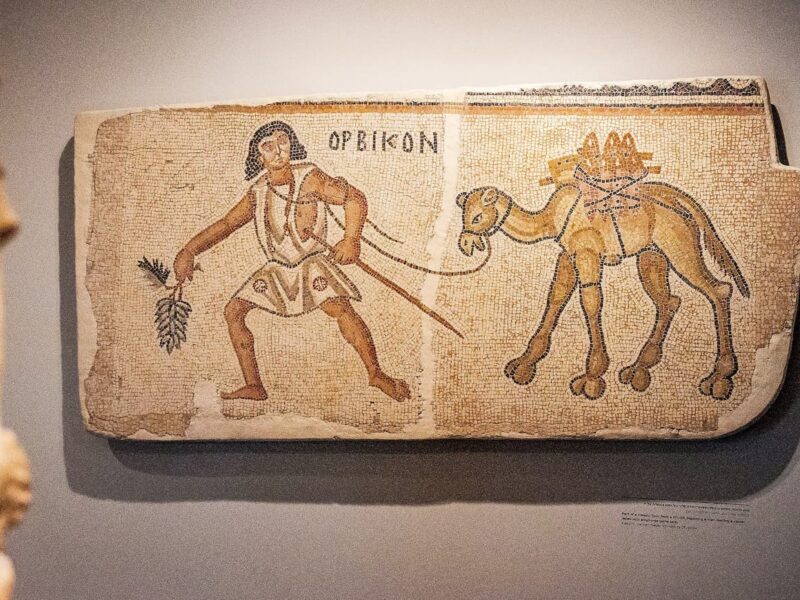

It was called Sapuna, which is the oldest known name, of Semitic origin. The Hurrians and later the Hittites knew it as Hazzi, believing it to be the dwelling place of their storm god, Teshub.

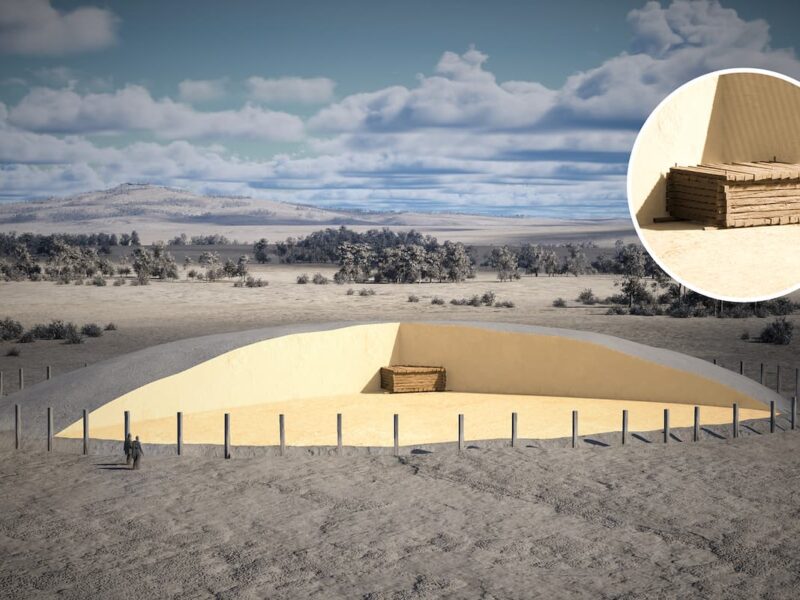

The Canaanites believed that the god Baal lived on its summit, in a palace built with blue lapis lazuli and silver alongside the goddess Anat. There’s no trace of the palace, but at its peak, a massive mound of ashes and debris was found in the early 1930s, about 55 meters wide and 8 meters deep, which could be the remains of an ancient sanctuary.

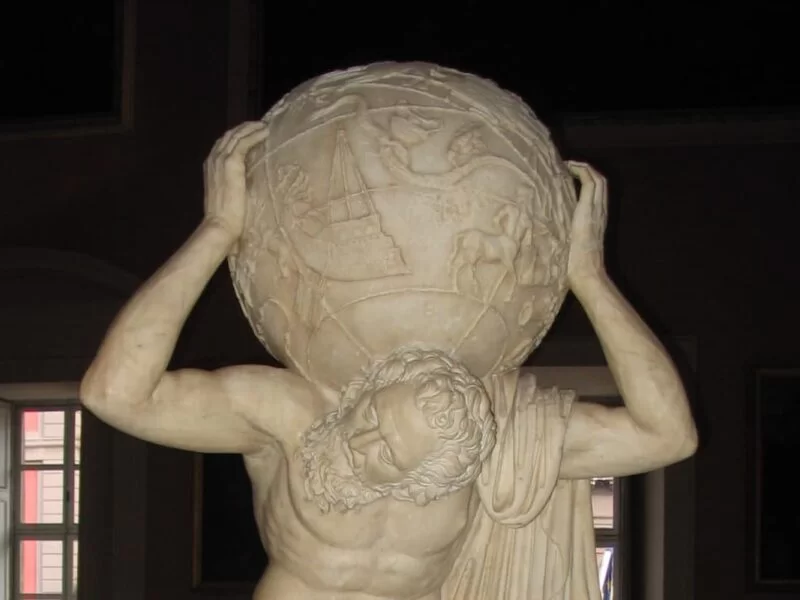

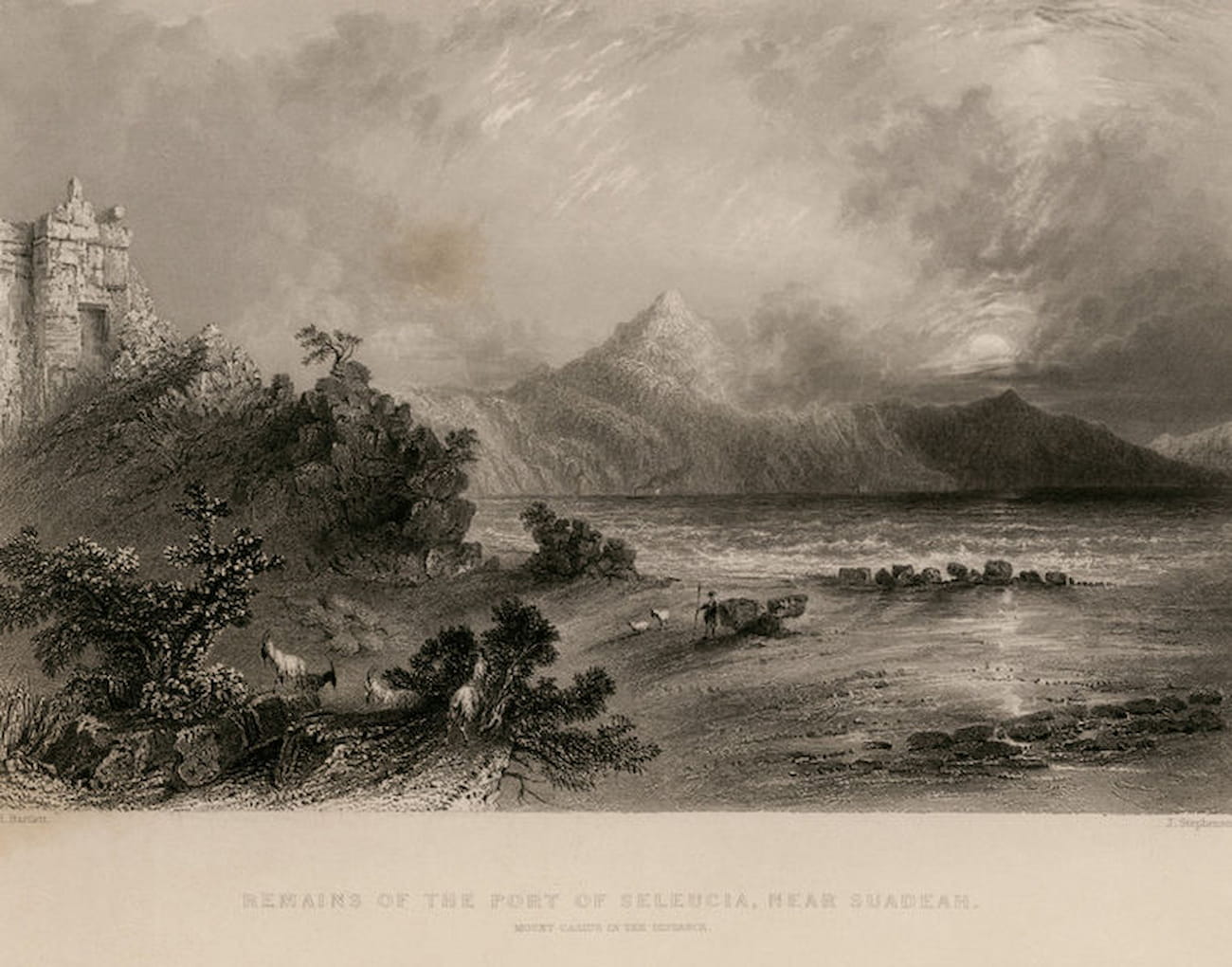

The Greeks called the mountain Mount Kasios (the Romans, Mount Casius), assimilating the worship of the god Zeus Kasios. It is known that they built a sanctuary there because bricks with the name of Zeus Kasios were found reused in the Christian monastery on the eastern slope of the mountain.

But before that, around 300 B.C., Alexander’s successor, Seleucus I Nicator, climbed to the summit to make sacrifices to Zeus Kasios, and tradition tells that an eagle took part of the offering (meat) and dropped it nearby on the coast, where a small settlement already existed. There Seleucus founded his new city, Seleuceia.

Later, in the winter of 115 A.D., Trajan was in Antioch, where Hadrian had fixed his residence as imperial legate. On December 13th, a great earthquake destroyed the city, but both managed to escape.

Trajan fled through a window of the room where he was staying. Some being, taller than human, had approached him and guided him forward, so he escaped with only a few minor wounds; and as the shocks continued for several days, he lived outdoors in the hippodrome. Mount Casius itself shook so much that its peaks seemed to bend and break and fall onto the city itself. Other hills also settled, and much water that did not exist previously came to light, while many streams disappeared.

Dio Cassius, Roman History 68.25

Of course, Trajan attributed his salvation to Jupiter Casius (now with Roman name) himself, who would have guided him in his escape. So, he climbed the mountain to offer the consequent sacrifices accompanied by Hadrian, who composed verses for the occasion describing the god, quite appropriately, as dark and cloudy.

Hadrian himself, already emperor, would return in the year 130, because during the years he lived in Antioch he had heard of another of Mount Casius’s curious features: as it rises so steeply above sea level, from its peak, one could contemplate a unique spectacle; for about five minutes, the sun rose from the East while the plains and the sea to the West remained completely dark. This happens, according to Pliny the Elder, at 3 in the morning.

Hadrian climbed the mountain in the darkness of the night to arrive in time to contemplate the unusual spectacle that awaited him at the summit at dawn. Sources tell that as he prepared to honor Jupiter Casius with a sacrifice, a lightning bolt killed the animal and left the officiant badly injured, although experts give little credence to this incident.

The last emperor to climb Mount Casius was also the last pagan emperor before Christianity ended the old Roman religion. Julian the Apostate, ascended in the spring of the year 363 A.D., hoping, like Hadrian, to see the fabulous sunrise.

Libanius, a master of rhetoric who was his intimate friend (and of whom about 1,544 letters survive, more than even from Cicero himself), says that Julian not only saw the sunrise but saw Jupiter Casius in person.

Once, having ascended Mount Casius, to Jupiter Casius, at a certain noon, he saw the god visibly, and upon seeing him, he stood up, and received from him a warning, by which he escaped for the second time from an ambush

Libanius, Funeral Oration for Emperor Julian, Or.18.172

To counteract the influence of the pagan sanctuary, to which pilgrims continued to come to worship Zeus (or Jupiter) Casius, a Christian monastery was built in the middle of the ascent path to the summit. And so, gradually, after more than seventeen hundred years, the god who dwelled at the top of Jebel Aqra was left alone.

But before, as the mountain sinks its foundations into the sea, Zeus Casius was venerated as the protective deity of sailors and thus extended to Egypt, Greece, and beyond. Even Emperor Marcus Aurelius thanked him for victory in a battle in distant Germania.

Excavations were carried out at the summit in 1937, but only reached 1.8 meters deep, which coincides with the Hellenistic strata.

The site was closed during World War II, and has not been excavated again, as it is in a militarized zone on the Turkish-Syrian border. Who knows what secrets it will keep.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on March 13, 2024. Puedes leer la versión en español en La montaña que atrae a las tormentas y a la que ascendieron tres emperadores romanos

Sources

Robin Lane Fox, Travelling Heroes: Greeks and their myths in the epic age of Homer | Peter Van Nuffelen. (2006). Earthquakes in A.D. 363-368 and the Date of Libanius, Oratio 18. The Classical Quarterly, 56(2), 657–661. jstor.org/stable/4493463 | Libanius, Julian the Emperor | Wikipedia

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.