Along with Journey to the Center of the Earth, Five Weeks in a Balloon, and some others, An Antarctic Mystery has always been one of my favorite novels by Jules Verne; partly because of the work itself and partly due to the magnificent comic book adaptation by artist José Duarte Minarro in 1973 for that priceless collection from Spanish publisher Bruguera, titled Juvenile Literary Jewels. The book, interestingly, is a continuation of a classic by another equally famous author, Edgar Allan Poe, who also influenced a third writer, H.P. Lovecraft, who includes several references in his work At the Mountains of Madness.

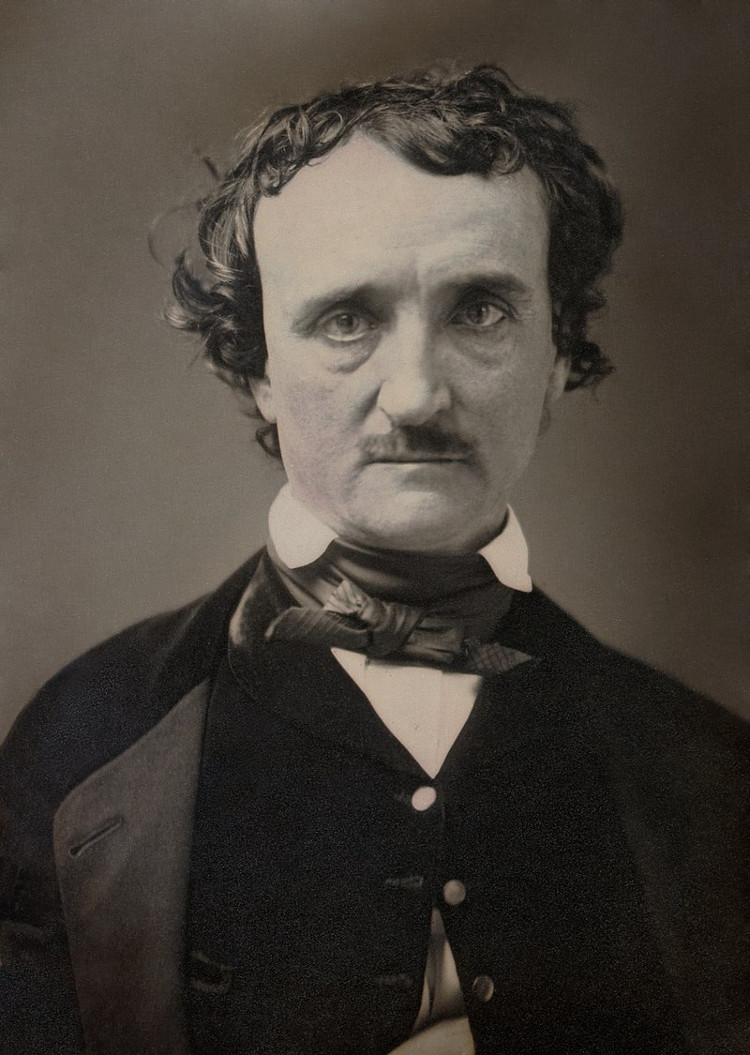

Obviously, I’m referring to The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, the only proper novel by Poe (the rest of his literary production consists of short stories and poems). Published in a volume in 1838 (it had previously been released in installments), the plot is a feverish combination of reality and fantasy in which horror is expressed in an unusually raw manner, with passages of cannibalism and even science fiction, reflecting the mystery that the polar regions held at a time when the first scientific expeditions to such corners of the planet were being organized.

The Arthur Gordon Pym that gives the title to the book is, as Salvador Vázquez de Parga says, one of the first natural-born adventurers in literature, inspired by the desire for freedom, love of danger, and the sense of fantasy. However, with a terrible eye for choosing the ships he boards as a stowaway. In the first, he ends up shipwrecked. In the second, he has to witness a mutiny from his hiding place and a new sinking, from which he survives with other companions, only to end up fighting each other at the terrible prospect of starving to death on the high seas after seeing a gruesome ghost ship full of rotting corpses pass by.

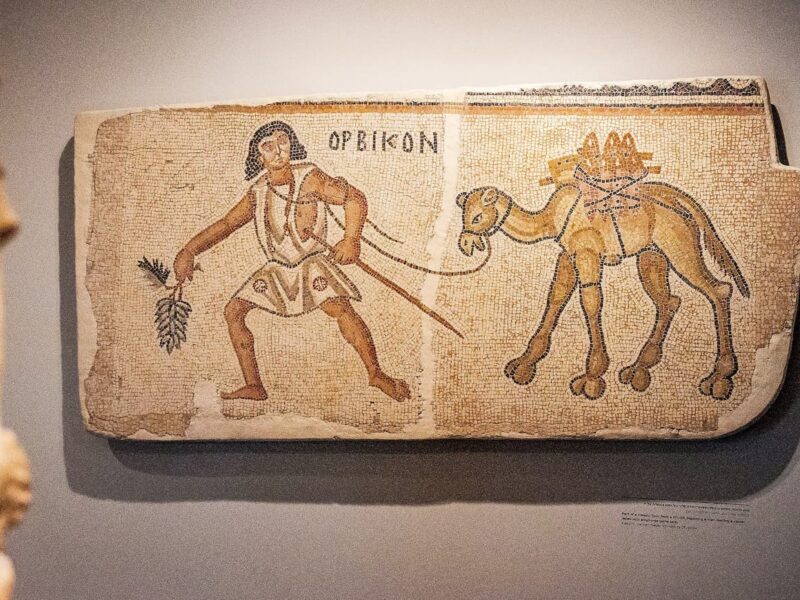

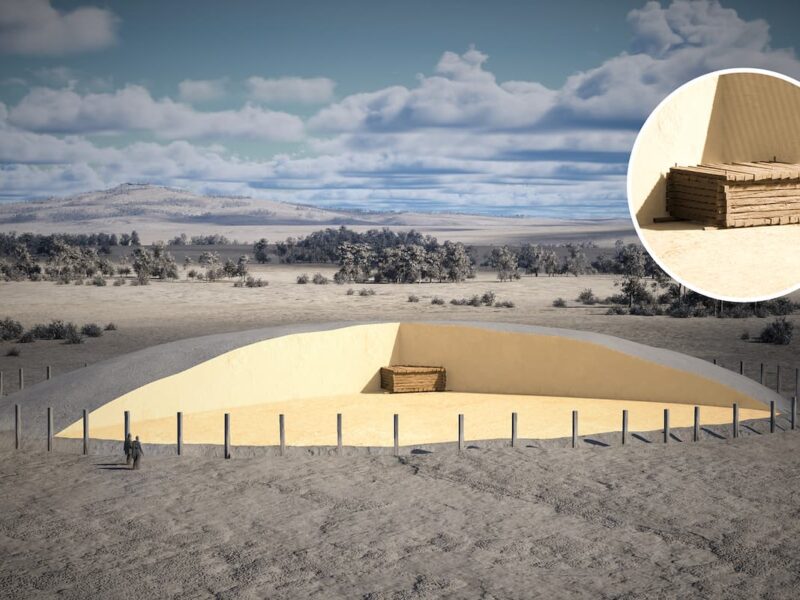

Pym is rescued, but he himself expresses that I never felt a more ardent desire for the violent adventures that stir the life of a sailor than a week after our miraculous salvation. And, consequently, for the third time, he enlists in a schooner to hunt seals in Antarctic waters. But the ship reaches Tsalal Island, a strange land with mild climate, thick and multicolored water, and a strange labyrinth among the mountains with hieroglyphics carved in stone. Additionally, a tribe of black race lives there, unaware of the color white because nothing there has it. This people murders the crew except for the protagonist and his friend, who escape in a canoe, venturing into a milky and warm sea.

That last part of the story becomes almost dreamlike, nightmarish, and culminates when the characters, overshadowed by threatening giant birds while being carried away by a strong current amid completely anomalous weather conditions—increasing heat, colossal clouds of steam, absence of night and ice, a rain of ashes—reach the abrupt end of the story, as unsettling as it is full of intrigue:

And suddenly we found ourselves precipitated into the depths of a waterfall, and a chasm opened before it to receive us. But as we passed, a human figure emerged, veiled, with dimensions much larger than any inhabitant of the Earth, and with skin as white as snow.

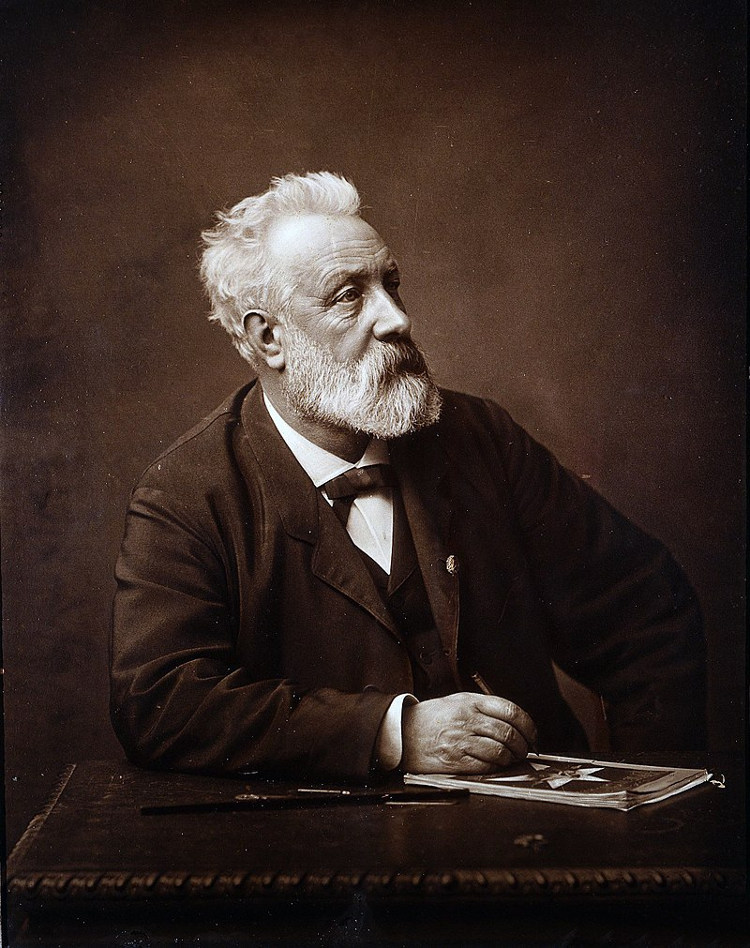

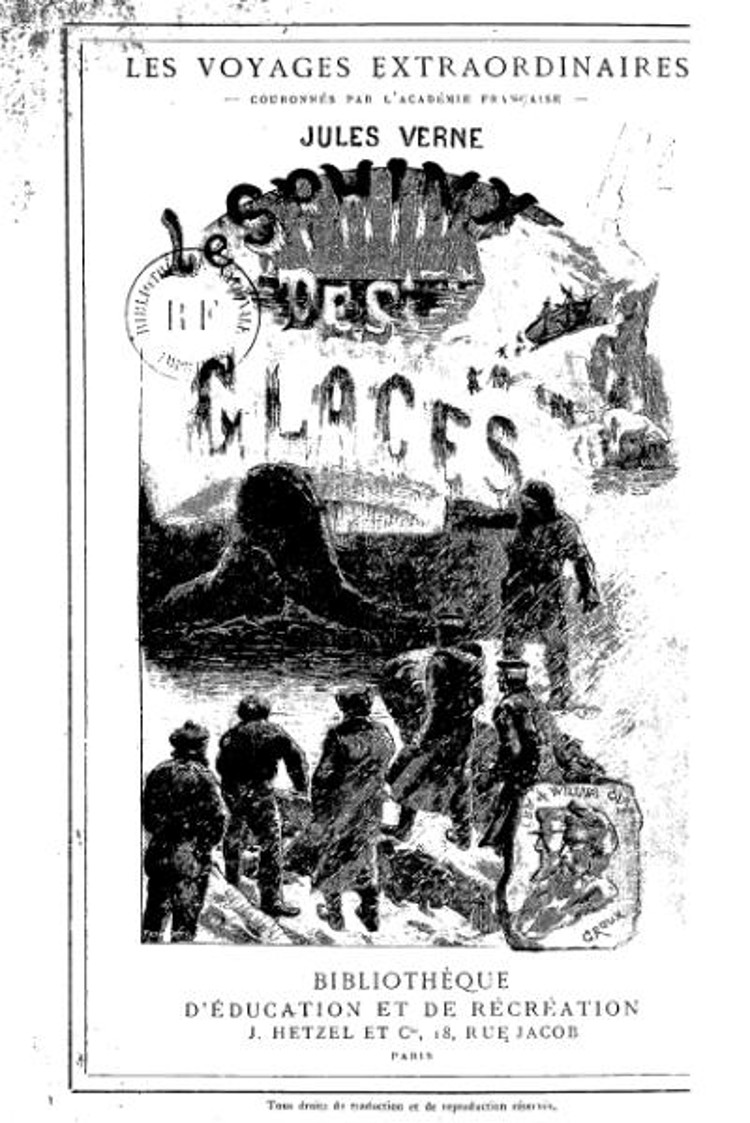

That was the strange motif that Jules Verne would recover fifty-nine years later to turn it into the centerpiece of the plot of An Antarctic Mystery (Le Sphinx des glaces, The Sphinx of the Ice Fields). He wasn’t the only one to do so, as Poe’s novel, despite receiving rather negative reviews, had an enormous influence, directly or indirectly, on many writers: Melville and his Moby Dick, Charles Romeyn Dake with A Strange Discovery, the aforementioned Lovecraft with At the Mountains of Madness, Paul Theroux with The Old Patagonian Express, Baudelaire in his poem Journey to Cythera, and many more.

The fact is that, in 1864, Verne had written Edgar Poe and His Works, a study of the genius from Baltimore in which he highlighted the fact that the story of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket had an open ending—or rather, it remained inconclusive—with the characters rowing in those inscrutable latitudes, drawn by an invisible force.

And the Frenchman wondered, Who will continue it? One bolder than I and more daring to delve into the realms of the impossible. In reality, there were few more suitable than him, but he thought about it for more than three decades, and when he finally started, he already had some experience in polar themes, having published The Adventures of Captain Hatteras in 1864 and The Fur Country in 1872, although they took place in the Arctic.

Thus, in 1897, he released An Antarctic Mystery, first in installments in a family-oriented magazine called Le Magazin d’éducation et de récréation and then in two volumes. By then, he was in his final stage, suffering from blindness—due to diabetes that would eventually send him to the grave in 1905—that slowed down his prodigious creative pace without interrupting it. Perhaps this physical limitation prompted him to write sequels to previous works: Verne had recently written the continuation of his own novel, The Purchase of the North Pole, in which he recounted new adventures of the protagonists of From the Earth to the Moon; this time planning to shoot a giant cannon that would change the axis of the planet and melt the polar ice to exploit the mineral riches of its subsoil.

The premise of An Antarctic Mystery is that of a sequel that takes place shortly after what Poe narrated. He had suggested that his story should continue in an underground world, but Verne already had Journey to the Center of the Earth in his curriculum, and it was not a matter of repeating himself.

So, once again, he opted for the icy scenario, and in this way, the reading introduces us to a new protagonist, an American geologist named Jeorling, who, wanting to study the South Pole, joins the expedition that Captain Len Guy organizes in search of his brother William, lost in the Antarctic Ocean.

William was the one who commanded the ship on which Arthur Gordon Pym traveled, and his diary, found on the corpse of a crew member, reveals that he is still alive with a handful of survivors on Tsalal Island. They must be rescued.

Warning: Spoilers Ahead

The journey begins in the Kerguelen Islands, and little by little, they venture into that edge of the world, facing either bad weather, floating ice, or the reverential fear that sailors have of an Ice Sphinx, which attracts ships to their destruction. Events escalate when the crew, gripped by terror, mutinies, and a huge iceberg takes out the schooner by turning on itself.

Some manage to survive, but their boat is dragged towards the threatening sphinx by that mysterious force described by Poe and against which they cannot fight.

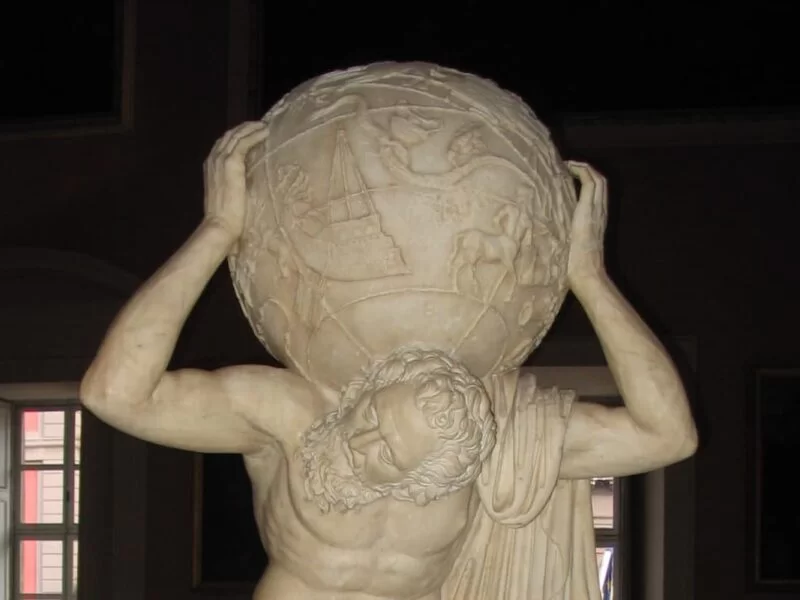

And then, a quarter of a mile away, a mass rose that dominated the plain in an extent of 50 fathoms over a circumference of 200 to 300. By its strange shape, that mass seemed like an enormous sphinx, with the torso erect, the legs extended, crouched, in the attitude of the winged monster that Greek mythology has placed in the path of Thebes. Was it a living animal, a gigantic monster, a mastodon a thousand times larger than those huge elephants of the polar regions whose remains are still found? In the state of mind we were in, one could have believed so, and also believed that the mastodon was about to hurl itself upon our boat and crush it between its claws.

Finally, and paradoxically, they are helped by those they were going to rescue, and Jeorling discovers the mystery of the place: that force is magnetic because the Ice Sphinx turns out to be nothing more than a large rock magnetized by induction from polar electrical discharges, combined with an underground metallic vein in the heart of the figure.

A gigantic magnet, in short, that attracts everything metallic, from the fittings of the ships to tools and weapons, as shown by the multitude of pieces attached to the rocky wall, like the hanging harpoons on the back of Moby Dick:

So, there was a magnet of prodigious intensity, and we had entered its attraction zone. Before our eyes, one of those surprising effects had occurred that had hitherto been considered as fables. Who has ever admitted that ships can be irresistibly attracted by a magnetic force and that their fittings escape, and their boats open, and the sea swallows them for this reason?… And yet, so it was… (…) Those continuous currents to the poles, which agitate the compasses, must possess extraordinary influence, and it would be enough for a mass of iron to be subjected to their action to be transformed into a magnet of power proportional to the intensity of the current.

And at the feet of this, they find something else: the frozen body of Arthur Gordon Pym still carrying a rifle that, instead of saving him, condemned him.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on June 17, 2019. Puedes leer la versión en español en La esfinge de los hielos, cuando Julio Verne escribió la secuela de una obra de Poe

Sources

La esfinge de los hielos (Julio Verne)/Narración de Arthur Gordon Pym (Edgar Allan Poe)/Héroes de la aventura (Salvador Vázquez de Parga)

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.